During the turbulent days of empire the colony of Seychelles was home to quite a few exiles. TONY MATHIOT tells the story of the banishment of one particular King whose exiles have had an enduring social impact on the island where he stayed. …for twenty-four years.

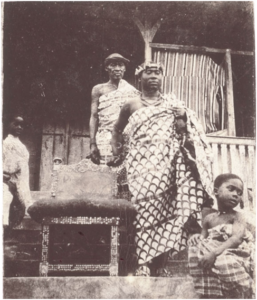

He arrived in Seychelles aboard the SS Dwarka on Tuesday 11th September of 1900; accompanied by 52 other prisoners, among them were his mother, his father, his brother and his three wives. Garbed in his tribal garments of leopard skin, the 27 year old ex-ruler of the Ashanti Kingdom must have commanded undue curiosity among the inhabitants who were at the Long Pier to witness the arrival of the Ashanti prisoners. Notwithstanding his distinctive appearance, the man resembled hundreds of Seychellois men, who were in fact, liberated Africans who had arrived on the shores of Seychelles in the late 1860’s as children of slaves, rescued from Arab dhows by ships of the Royal Navy.

He arrived in Seychelles aboard the SS Dwarka on Tuesday 11th September of 1900; accompanied by 52 other prisoners, among them were his mother, his father, his brother and his three wives. Garbed in his tribal garments of leopard skin, the 27 year old ex-ruler of the Ashanti Kingdom must have commanded undue curiosity among the inhabitants who were at the Long Pier to witness the arrival of the Ashanti prisoners. Notwithstanding his distinctive appearance, the man resembled hundreds of Seychellois men, who were in fact, liberated Africans who had arrived on the shores of Seychelles in the late 1860’s as children of slaves, rescued from Arab dhows by ships of the Royal Navy.

Prempeh I (1872-1931) the Asantehene, Kwaka Dua III, Agyemang Prempeh of the Oyoko Clan and his dozens of followers had been banished to Seychelles. The oldest among them was Kwamin Apia, the 72 year old ex-chief of Manpoug and the youngest was his own newborn baby girl who was about two months. Little did he know that for twenty-four years he would be in the custody of five successive British Governors and that he would be the subject of epistolary exchanges between these Governors and eleven Secretaries of State. The exiled King must certainly have gazed wistfully up at the forested mountains above Victoria. They must have reminded him of the primeval forests of his beloved kingdom…

It was on the 26th July of 1900 that Joseph Chamberlain (1836-1914) the Secretary of State for the Colonies inquired if arrangements could be made for the detention of the Ashanti Chief and his cohort who were then in the their third year of captivity and were in confinement in Sierra Leone. Thus, Ernest Bickham Sweet-Escott (1857-1941) who had just been appointed as the administrator of Seychelles (which was then a Dependency of Mauritius) in August of 1899 found himself confronted with his first major colonial problem. Way back in 1877, the Sultan of Parak had been sent to exile in Seychelles where he stayed until 1895. The five commissioners Charles Spencer Salmon (1832-1896), Arthur Havelock (1844-1908), Francis Blunt (1837-1882), Arthur Cecil Barkly (1843-1890) and Thomas Risely Griffith had accepted his custody as an integral aspect of their colonial responsibilities. Likewise, Sweet-Escott decided to take this unexpected turn of events in his stride. So, on the 3rd of August of 1900 ‘The West African Political Prisoners Ordinance’ was passed in the Legislative Council. This was a prerequisite procedure to legalize the banishment of the Ashanti prisoners and to justify the implications that this would entail.

On the 24th August, Chamberlain confirmed that ‘Prempeh and followers’ had embarked on SS Dwarka at Sierra Leone on the 20th and assured Sweet- Escott that all expenses would be re-imbursed by the Government of the Gold Coast. On the 11th of August, an agreement of lease between the proprietor, Jean-Baptiste Adam and the Administrator, for a house at Le Rocher at Rs.80 per month was signed. The house, which was a timber structure with a pitched roof, was located on a 17 acre property on the east of Mahé, about two miles away from Victoria. It was there at the Asante Camp that Prempeh and his chiefs and their families were accommodated whilst the rest of the party occupied huts near the La Misère crossroads, a site which was called ‘African Camp’. The house which had six rooms and a verandah was sparsely furnished. The basic articles required for the king were: 5 tin mugs, 6 buckets, 14 cooking pots, 4 hurricane lamps, 6 brooms and 2 brushes. His nine chiefs were supplied with 25 mats, 9 lamps, 20 plates, 20 bassins, 22 cooking pots, 9 buckets, 9 chairs, 18 spoons, 9 tin mugs, 18 blankets and 18 mattresses. The food of the Ashanti prisoners consisted of rice, plantain, sweet potato, beans and a variety of vegetables. Not much different from what they were used to eating back home. One of their most popular dishes was called banku, a mixture of maize dough and cassava. They also mixed spinach with palm oil to make a sauce that was eaten with boiled fish or vegetables. At Asante Camp, Prempeh and his entourage cultivated their own vegetables and also reared pigs and hens. The wives of the chiefs were allowed to go to the market and shops in Victoria to sell their produce and to buy commodities.

It must have certainly caused quite a sense of perturbation to Prempeh, not knowing for how about long his exile in Seychelles would last. But given the reason for his deportation, his repatriation, depended of course on developments in Kumasi, the capital of his Empire. But why, why was an African King of one of the greatest Kingdoms in Africa banished to a small remote British Colonial outpost in the first decade of the twentieth century? Why?

It must have certainly caused quite a sense of perturbation to Prempeh, not knowing for how about long his exile in Seychelles would last. But given the reason for his deportation, his repatriation, depended of course on developments in Kumasi, the capital of his Empire. But why, why was an African King of one of the greatest Kingdoms in Africa banished to a small remote British Colonial outpost in the first decade of the twentieth century? Why?

To find the answer, we must search far away and rummage out the chapters of the mid-17th century…

…When almost the entire modern nation of Ghana was dominated by the Ashanti Empire. And indeed, nowhere else in Africa have existed such protracted antagonism between Africans and Europeans than here at the Gold Coast where enmity between the Ashanti people and the British which began in 1760 culminated in the first Anglo-Ashanti War of 1824. The Ashanti repulsed the British forces and killed Sir Charles McCarthy (1764-1824), their Commander and Governor of the Gold Coast. In 1482, the stretch of the Atlantic coast on the southern shore of what is now the Republic of Ghana became known as Gold Coast because Portuguese explorers discovered gold there.

The Ashanti kingdom was founded by Osei Tutu. It was a confederacy of many tribal states located in the forest region of southern Ghana in West Africa. Obuassi in the south-west was the centre of the goldmining industry. These tribes included Adjisu, Kokofu, Nkwanta, Ofinsu, Bekwai, Mampong and Nsuta. The capital was Kumasi. Their languages were Twi and Akan. Their currency was gold dust. Later, they used cowries. They controlled access to long-distance trade liking the Mediterranean Sea, across the Sahara Desert, with the Atlantic Ocean west of the African coast. The king of Kumasi exercised authority over the whole Empire, and all these states acknowledged the sovereignty of the ruler of Kumasi. Each Asanthene was enthroned on the Golden Stool which symbolized the supreme power of the King. The crown descended to the King’s brother or his sister’s son not to his own offspring. The Empire which was known for its military prowess, sophisticated hierarchy and social stratification traded in gold, ivory and slaves which were sold to, first Portuguese and later Dutch and British traders. Osai Tutu and his successors Osai Apoko (1731), Osai Tutu Quamina (1800), Osai Okoto (1824), Kwaka Dua (1838), Kofi Kari kari (1867) and Mensa Bonsu (1884) maintained the expansion and the defense of the Empire, having to contend with the opposition of the autonomous Fante Chiefdoms on the coast against which the Ashanti people competed for commercial ventures with European traders. It was at the height of imperial rivalries and colonial expansionism among the European nations that the Ashanti had to face its greatest threat.

After the war of 1824, the Ashanti was desperate to control the economy against the bitter resistance of the coalition of the Fanti states of the coastal regions who had the support of the British. Periodic invasions of the Gold Coast region were launched in a bid to gain access to European traders.

After the war of 1824, the Ashanti was desperate to control the economy against the bitter resistance of the coalition of the Fanti states of the coastal regions who had the support of the British. Periodic invasions of the Gold Coast region were launched in a bid to gain access to European traders.

British presence on the Gold Coast had been established in 1621 with the appointment of a Governor, Sir William St. John. However, the territory officially became under British Administration in 1874 after the third bloodiest Anglo-Ashanti war 1873-1874. This came about when the Ashanti Forces launched a brutal attack on the Fanti chiefdoms on the coast. In order to enforce its dominance in West Africa and pre-emptively control the territory less the French succeeded in colonizing it, the British insidiously capitalized on the discord between the Fanti tribes and the Ashanti. Consequently, it redounded to their advantage by using the constant Ashanti threat, to convince the coastal peoples to accept British control. So when on the 22nd January of 1873, an Ashanti force crossed the prah and invaded the British protectorate of the Gold Coast, slaughtering many Fanti people, drastic measures were taken to exact revenge for the attack. Sir Garnet Joseph Wolseley (1833-1913) was sent on a military expedition to Kumasi. After ferocious fighting, Asantehene Kofi Kari Kari accepted defeat and a peace treaty was signed. Wolseley was installed as Governor of the Gold Coast.

Humiliated by the defeat and in resentment of the peace treaty, the Ashanti deposed Kofi Kari Kari and replaced his brother, Mensa Bonsu on the Golden Stool. He was in turn deposed in a revolution in 1883 and was replaced by Kwaka Dua II who died within a few months after being ‘enstooled’. After a protracted civil war among many of the Ashanti dependent states, Prince Prempeh who took the name of Kwaka Dua III was chosen King of the Ashanti. He was 16 years old. His father Nana Kwasi Gyambibi was the son of Kwaka Dua I the Asantehene from 1834-1864.

Of course, Prince Prempeh had inherited a kingdom which was in the throes of decline. For the first few years of his rule, Prempeh’s priority was to reunite the confederacy and revive the Ashanti Empire back to its former glory. This was to the great discontent of the British, who had been anticipating the disintegration of the Ashanti Empire would provide the opportunity for them to assert their authority. Indeed, their disenchantment was short-lived. In 1893, Ashanti Forces invaded the territory occupied by the tribes of the protectorate. This incensed the British who immediately dispatched a mission to Kumasi with the aim of convincing Prempeh I to accept the presence of a British resident at Kumasi, who would arbitrate on disputes between the Ashantis and Fanti tribes. Unsurprisingly, Prempeh refused to submit his fragmented kingdom to the imposition of colonial rule. But, all odds were against him. The British resorted to a more aggressive alternative in order to enforce their demands. A British army under the command of Colonel Sir Francis Scott was dispatched to Kumasi. On the 17th January of 1896, the British arrived at Kumasi without encountering any opposition from the Ashanti. The twenty-five year old Asanthene had the presence of mind to realise that he had no hope of standing up to the army of the British Empire, and he didn’t want his people to be slaughtered by British soldiers. With characteristic Ashanti panache and aplomb, he surrendered. On the 20th January of 1896, Prempeh I, together with his mother, father, brother, several Ashanti chiefs and their wives and children were arrested and detained at Elmina Castle until 1897, when they were moved to Freetown in Sierra Leone. On the 27th August of 1896, Ashanti became a British Protectorate. Sir Donald Stewart was appointed Chief Commissioner of Ashanti. Under orders in council of September 26th of 1901, the country was formally annexed to the British Domions, to become part of the Gold Coast with the Governor of the Gold Coast being appointed Governor of Ashanti but which was administered by a Chief Commissioner. Sir Mathew Nathan who had been appointed Governor of the Gold Coast on the 17th December of 1900 became the first Governor of Ashanti. But that was after the British Forces had to contend with a last fierce revolt led by the defiantly fearless Queen Mother of Ejisu named Ya Asantewaa (1863-1921). From March to September of 1900, she and her band of intrepid Ashanti warriors engaged British forces in a last desperate attempt at saving Ashanti dignity. They were defeated. Ya Asantewaa and 14 others who were deemed ‘criminally dangerous’ were deported from Ashanti and banished to Seychelles.

So it was an austere-looking 70 year old woman and 14 weary and glum men who arrived at Mahé aboard the SS Dwarka on Saturday 22nd June of 1901. Among them were Edu Kofi (1831-1921) King of Borumfu, Kojo Enchi, Chief of N’Kawe, Kofi Kuma (1844-1904) Chief of Tekimantia, Kwami Efilfa (1847-1907) the chief executioner of Kumasi. Most of them would die in Seychelles, just like most members of Prempeh I’s compatriots who had arrived four months earlier. Indeed, there was death during the first days of their exile as there would be death during the last days. The first Ashanti prisoner to die was Kwaku Foku who passed away on the 16th September of 1900, a mere five days after his arrival. He was 55 years old. And there were many births, as much as anyone would have anticipated among a group of exiled prisoners from a polygamous and pro-natalistic country. Prempeh himself had seventeen children with his 3 wives between 1901 and 1917. A baby boy named Kwakudum who was born on the 26th July of 1905, died twelve days later. On Saturday 7th of July, one of his wives, Amah, gave birth to twin girls; Alexandra Amah Sewa Sekehini and Victoria Amah Sewa Sekehini were named after Queen Victoria Alexandrina (1819-1901). Apparently, he harboured no grudge against the matriarch of the very Empire that had deposed him!

The year that Prempeh arrived in Seychelles, the archipelago was ruled as a Dependency of Mauritius. The population was approximately 19,000 inhabitants, most of whom earned their livelihood working on coconut estates or on vanilla plantations since at that time coconut oil and vanilla had substantial export value in the overseas market. Roads and bridges were being constructed all around Mahé to facilitate the peregrinations of the inhabitants, among whom only a few, mostly landowners could afford the luxury of horses. The capital town of Victoria was getting the necessary infrastructures that befitted any small colonial outpost. Even the pier, dating back to the 1840’s was being extended because Port Victoria then accommodated ships of the Messageries Maritime which provided the only contact with the outside world. Clearly, Prempeh did not accept his exile with fatalistic resignation, although by then he must have been painfully familiar with the modus operandi of colonial authority. Because, merely a year after he arrived in Seychelles, he and his compatriots sent a first petition to Sweet-Escott, on November 5th of 1901, asking to be allowed to return to Ashanti. A similar entreaty was sent in late 1902. In fact, throughout his entire duration of his exile, Prempeh sent regular petitions and requests to the Governor. Most of these were ingratiating lamentations tinged with fawning expressions of repentance. In 1907, he asked Walter Edward Davidson (1859-1923) to appoint someone to teach him to read and write his Ashanti language. In 1908, he asked the same Governor to send back two of his wives to Gold Coast. In 1913, he wrote to Governor Charles Richard O’Brien (1859 – 1935) asking ‘for a leave of six months to visit the great city of London on board a British Warship’! He kept making demands for repatriation until 1921.

The year that Prempeh arrived in Seychelles, the archipelago was ruled as a Dependency of Mauritius. The population was approximately 19,000 inhabitants, most of whom earned their livelihood working on coconut estates or on vanilla plantations since at that time coconut oil and vanilla had substantial export value in the overseas market. Roads and bridges were being constructed all around Mahé to facilitate the peregrinations of the inhabitants, among whom only a few, mostly landowners could afford the luxury of horses. The capital town of Victoria was getting the necessary infrastructures that befitted any small colonial outpost. Even the pier, dating back to the 1840’s was being extended because Port Victoria then accommodated ships of the Messageries Maritime which provided the only contact with the outside world. Clearly, Prempeh did not accept his exile with fatalistic resignation, although by then he must have been painfully familiar with the modus operandi of colonial authority. Because, merely a year after he arrived in Seychelles, he and his compatriots sent a first petition to Sweet-Escott, on November 5th of 1901, asking to be allowed to return to Ashanti. A similar entreaty was sent in late 1902. In fact, throughout his entire duration of his exile, Prempeh sent regular petitions and requests to the Governor. Most of these were ingratiating lamentations tinged with fawning expressions of repentance. In 1907, he asked Walter Edward Davidson (1859-1923) to appoint someone to teach him to read and write his Ashanti language. In 1908, he asked the same Governor to send back two of his wives to Gold Coast. In 1913, he wrote to Governor Charles Richard O’Brien (1859 – 1935) asking ‘for a leave of six months to visit the great city of London on board a British Warship’! He kept making demands for repatriation until 1921.

All the Governors who were posted in Seychelles during his long exile showed sympathy and respect to Prempeh and his followers. They saw him as an unfortunate victim of colonial circumstances, and they all ensured that he experienced the minimum of hardship and they always had a courteous regard and a humanitarian concern for his welfare.

Right from the beginning, Sweet-Escott made it obviously clear that Seychelles owed the deposed King and his retinue a measure of colonial hospitality when he invited Prempeh and his mother and all his ex-chiefs to attend a levée on Saturday 9th November of 1901 at the court house in honour of King Edward VII’s (1841-1910) 60th birthday. The following year, on Thursday the 14th of August, they were invited to a similar function in celebration of King Edward VII’s coronation. Seychelles became a separate colony on the 31st August of 1903, and on Wednesday 1st April of the same year, Prempeh and his entourage attended the ceremony of the unveiling of the Victoria Clock Tower.

Life at the Ashanti camp was calm and peaceful but it was not without its shenanigans and occasional altercations. Even though Prempeh and his compatriots were left to administer their own affairs, a Senior Police Officer was appointed to ensure that peace and discipline were maintained in the camp. During the first decade of their exile, it was a Mauritian Inspector of Police Louis Arthur Tonnet (1866-1930) who had the responsibility of supervising the Ashanti prisoners. A major incident happened on Thursday 11th January, when the wife of Kojo Apia Ex-chief of Manpong, Mensa, fought with one of Prempeh’s wives, Morbin, who was pregnant. The latter was struck on the head with a club and had to be taken to hospital. The Government of Gold Coast sent monthly allowances to all the Ashanti prisoners according to their ranks. Prempeh got Rs. 232.50, George Assibi, ex-chief of Kokofu got Rs. 69.75cts while the rest got Rs. 57.97cts. In 1921, an increase of 20% in their allowances was sanctioned by the Government of the Gold Coast due to the rising prices of foodstuffs in the colony.

On the 29th may of 1904, Prempeh was baptised into the Anglican faith by Rev. Harold Johnson. From then on, the Asanthene referred to himself as ‘King Edward Prempeh’. He and his mother and some of the Ashanti prisoners attended Sunday mass regularly at St. Paul’s church in Victoria. By then, most of the men who habitually dressed in the kente cloth known as nwentoma had gotten used to European Sartorial elegance, with Prempeh developing a taste for frock coats, tall hats and patent-leather boots!

Eventually, as it became obvious that their stay in the colony was not going to end anytime soon, quite a few of the prisoners found employment as labourers, washerwomen and rickshaw drivers.

Many of the Ashanti prisoners took on Seychelloise wives with whom they had many children. Paul kwamin Ankroma, the ex-chief of Telkeri who was among the fifteen “criminally dangerous” deportees in 1901 married a Seychelloise woman in 1907 who gave him six children, four sons and two daughters. Ex-chief Georges Assibi of Kokofu also had a Seychelloise wife with whom he had six children, fours sons and two daughters. Three of Pempeh’s sons, James, Alfred and Joseph married Seychelloise women with whom they had many children.

Prempeh was deeply concerned about the education of the children in the Ashanti Camp. At his persistent requests, on the 11th October of 1909, an infant school was opened at the camp after the Government of the Gold Coast paid the sum of Rs. 6000.00 (£400) for the cause. In 1912, there were forty-five children under the age of fifteen at the camp. The infant school accommodated children under the age of six. The older children attended St. Paul’s Church of England Girls’ School and the Victoria School.

During the early years of his exile, Prempeh’s literacy was nurtured by a Fante teacher who had been recruited to work as interpreter for the political prisoners. Timothy Korsah was assigned the task of teaching Prempeh how to read and write the English language. He proved to be a keen learner and manifested a liking for books and was often seen borrowing books at the Carnegie Library (est. 1910) in Victoria.

So the years passed, rather dawdlingly with little happening to offset the tedious life in the Ashanti Camp. Gradually, as they began to associate with the local inhabitants, Prempeh and his compatriots soon learned to speak the Seychellois Creole Language fluently. In fact, some linguists aver that the Ashanti prisoners introduced a few African words in the Creole Language while social Anthropologists also affirm that many aspects pertaining to knowledge of medicinal plants in Seychelles came from the Ashanti prisoners who learned from their grand parents. Knowledge passed down across generations in the jungles of the Ashanti Kingdom. Besides various governments and religious personalities, curiosity also lured quite a few scientist and journalists who happened to be visiting the Seychelles, to spend a moment at the Ashanti camp talking to Prempeh and his Chiefs. Like all the proprietors on Mahé, the Ashanti prisoners also engaged in the cultivation of vanilla vines which brought some revenue. During the First World War, a shortage of food in the colony compelled Governor O’Brien to enact an ordinance to provide for the increased cultivation of ground crops, such as maize, bananas, sweet potatoes and cassava. At the camp, sustenance agriculture ensured that the prisoners did not suffer from want of nourishment. However… There were moments of grief … On the 3rd September of 1917, Prempeh’s beloved mother Nana Yaa Akyaa passed away at 75 years old. Later, the same month, his 42 year old brother, Agyeman Badu died.

So the years passed, rather dawdlingly with little happening to offset the tedious life in the Ashanti Camp. Gradually, as they began to associate with the local inhabitants, Prempeh and his compatriots soon learned to speak the Seychellois Creole Language fluently. In fact, some linguists aver that the Ashanti prisoners introduced a few African words in the Creole Language while social Anthropologists also affirm that many aspects pertaining to knowledge of medicinal plants in Seychelles came from the Ashanti prisoners who learned from their grand parents. Knowledge passed down across generations in the jungles of the Ashanti Kingdom. Besides various governments and religious personalities, curiosity also lured quite a few scientist and journalists who happened to be visiting the Seychelles, to spend a moment at the Ashanti camp talking to Prempeh and his Chiefs. Like all the proprietors on Mahé, the Ashanti prisoners also engaged in the cultivation of vanilla vines which brought some revenue. During the First World War, a shortage of food in the colony compelled Governor O’Brien to enact an ordinance to provide for the increased cultivation of ground crops, such as maize, bananas, sweet potatoes and cassava. At the camp, sustenance agriculture ensured that the prisoners did not suffer from want of nourishment. However… There were moments of grief … On the 3rd September of 1917, Prempeh’s beloved mother Nana Yaa Akyaa passed away at 75 years old. Later, the same month, his 42 year old brother, Agyeman Badu died.

Moments of disgrace… in August of 1919, Prempeh’s son Alfred was dismissed from his employment as a clerk in the Public Works Department after he had stolen money from subscription funds set up to erect a memorial stone on the tomb of William Marshall Vaudin (1867-1919) the Superintendent of Public Works who had passed away on the 21st March of that same year.

And moments of pride…when his 18 year old son, John, travelled to Mauritius on the 27th January of 1921 to study for the priesthood. By 1922, when political circumstances in Kumasi made it possible for the Governor of the British protectorate C.H.Harper to consider the repatriation of the deportees provided they agreed to comply to certain conditions ‘that they will not allow themselves to be drawn into political affairs and that they will observe any restrictions as to their place of residence which the Government may consider it necessary to impose’ there were only four surviving members of the second batch of fifteen deportees.

It was from that moment on that the Ashanti prisoners began to harbour hopes of seeing their homeland again. One can only imagine the emotional upheaval that the promise of freedom created in the Ashanti Camp.

On the 12th November of 1922, the first batch of twenty-four persons left on SS Kargola, among whom only five were original deportees. The rest were children of ex-chiefs born in Seychelles. But unfortunately, Prempeh’s departure would not be imminent. In March of 1922, a little more than two decades after he arrived, Prempeh still pined for his homeland. In a letter he had written to the Governor of the Gold Coast, Frederick Gordon Guggisberg (1869-1930) imploring for him and his few remaining chiefs to be allowed to return, he promised “We shall not ask to be re-instated to our former places and we shall like to be a private civilian”. Winston Churchill (1874 -1965) who was Secretary of State (February 1922– October 1922) informed him that his release would be considered in two years time. It was Governor Sir Joseph Aloysius Byrne (1874-1942) who assumed his post on 26th September 1922 who had to handle the procedures regarding Prempeh’s release as colonial bureaucracy required. On the 12th May 1924, he informed Prempeh that the Secretary of State for the Colonies James Henry Thomas (1874-1949), had informed him that the Ex-King would be allowed to return to Ashanti in September provided that he return as a private individual and not as a chief and that he reside at or near Kumasi and not move outside the capital. Prempeh was at first reluctant to sign the formal acceptance of conditions of his repatriation, protesting against the stipulation that restricted his movements but the prospect that he was at long last going to see the ancient land of his birth, his beloved mother made him abandon his objection. He was asked to furnish a comprehensive list of all his entourage because no one was to be left behind who might become a burden to the revenue of the colony through inability to earn his or her livelihood. The list gave names, ages, sex, parents and relationship to the ex-King or to any of the original Ashanti Political prisoners and specified whether legally married or not. The prospect of freedom stirred up feverish activity, commotion and haste as all those who had Seychelloise concubines made hectic preparations to get married including 2 of Prempeh’s sons, Alfred and Fredrick. A couple of weeks before the departure, Kwami Jansah the 80 year old ex-chief of Batamia passed away, on the 28th of August. On the 14th of August, Prempeh wrote a farewell letter to the people of Seychelles_ “I have appreciated the kindness of one and all in this community…I shall never forget the unfailing courtesy and respect shown to me by all classes of the population”…which was published in the Reveil Seychellois.

On Tuesday 2nd September, Prempeh and his entourage were summoned to the Government House for Governor Byrne to wish them farewell and to tell them that “you will find your native country changed beyond recognition and prosperous to a degree that could never have been dreamt of 24 years ago…”

On the 13th September of 1924, Prempeh and 49 others left Seychelles aboard SS Karoa for Bombay. The oldest among them was the ex-chief, James Asafu Boachie. He was 96 years old. The youngest was a three months old baby girl, daughter Rose Amah Apia, daughter of Kojo Apia (1831-1911) ex-chief of Kumasi. Among them, on 13 were original deportees. On the 22nd September they left Bombay and travelled to Liverpool on SS Olympia. The party left Liverpool on SS Abinsi on 29th October. On Tuesday 11th November 1924, Prempeh arrived at Kumasi. He was then fifty- four years old.

But, not all of them left. James Prempeh, a son of the ex-king and his Seychelloise wife, Marie-Francoise Auguste remained in Seychelles. They had seven children. In 1941, one of their daughters, Suzy Mary married Andre King, the son of Billy King (1857-1934), one of the liberated Africans who was brought to Seychelles by the Royal Navy in the 1860’s. The couple had a son and a daughter…who themselves had many children…

So today, there are living in Seychelles great-grandsons and, great grand-daughters of a man who was once upon a time the King of Ashanti…

Credit: http://www.pfsr.org/